IN DEVELOPMENT

based on play “Calling Aphrodite” by Velina Hasu Houston which received its world premiere recently at International City Theatre, Long Beach, California.

Youth, dreams, and lives destroyed in Hiroshima. The story of two teenage sisters who survived the blast close to ground zero and how it affected their lives.

Houston is a Pinter Review Prize for Drama Silver Medalist for the play which also was a finalist for the American Theatre Critics Association Steinberg New Play Award for its 2007 world premiere. Calling Aphrodite has been embraced by The former Honorable Consul General of Japan of Los Angeles Kazuo Kodama as a “remarkable and appropriate exploration” of the Hiroshima experience. In 2008, Calling Aphrodite was presented at Tokyo Engeki Ensemble (TEE), Tokyo. TEE and Houston continue to collaborate toward an international presentation of the play in Hiroshima.

When I was nine we drove across the USA and visited Los Alamos where the bomb was created – two weeks later we were in Hiroshima. It affected me for for the rest of my life.

[slideshow_deploy id=’1952′]

by a Hiroshima survivor:

I am a hibakusha, a survivor of Hiroshima. In 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. I was 12 years old, a 7th grader at girls’ junior high school. I was exposed to the A-bomb at a point less than a mile away from the epicenter.

I am a hibakusha, a survivor of Hiroshima. In 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. I was 12 years old, a 7th grader at girls’ junior high school. I was exposed to the A-bomb at a point less than a mile away from the epicenter.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the skies were perfectly clear without a sign of clouds. As the sun of midsummer arose, the temperature began to rise rapidly. When the air-raid alarm sounded at 7:09 a.m. and was cleared at 7:31 a.m., the citizens gave a sigh of relief and started their activities. Many people had entered the city from neighboring towns and villages to work at dismantling buildings. About 350,000 people were believed to have been in the city on that day, including more than 40,000 military personnel.

There was no vacation for students during the war. Students of only 12 years old or so had to work day after day in factories or at building demolition sites. On that day, a total of about 8,400 junior high school boys and girls aged 12 to 14 were working on six building demolition sites.

After the all-clear signal was issued, we went back to work. A total of 500 girl students, 7th and 8th graders of our junior high school, were serving as mobilized students, clearing away demolished buildings. Forming groups of 4 or 5, we collected broken tile, glass and pieces of wood and carried them in baskets, shouting “Yosha, Yosha,” encouraging each other.

Suddenly my best friend, Takiko Funaoka, shouted, “I hear the sound of a B-29.” Never thinking it was possible, I looked up and there, high in the sky, the white vapor was trailing.

Then I caught a glimpse of an airplane flying away to the northwest. I thought I saw some luminous body drop from the tail of the plane. I quickly lay flat on the ground. Just at that moment, I heard an indescribable deafening roar. My first thought was that the plane had aimed at me.

I had no idea how long I had lain unconscious, but when I regained consciousness the bright sunny morning had turned into night. Takiko, who had stood next to me, had simply disappeared from my sight. I could see none of my friends nor any other students. Perhaps they had been blown away by the blast.

I rose to my feet surprised. All that was left of my jacket was the upper part around my chest. And my baggy working trousers were gone, leaving only the waistband and a few patches of cloth. The only clothes left on me were dirty white underwear.

Then I realized that my face, hands, and legs had been burned, and were swollen with the skin peeled off and hanging down in shreds. I was bleeding and some areas had turned yellow. Terror struck me, and I felt that I had to go home. And the next moment, I frantically started running away from the scene forgetting all about the heat and pain.

On my way home, I saw a lot of people. All of them were almost naked and looked like characters out of horror movies with their skin and flesh horribly burned and blistered. The place around the Tsurumi bridge was crowded with many injured people. They held their arms aloft in front of them. Their hair stood on end. They were groaning and cursing. With pain in their eyes and furious looks on their faces, they were crying out of their mothers to help them.

I was feeling unbearably hot, so I went down to the river. There were a lot of people in the water crying and shouting for help. Countless dead bodies were being carried away by the water – some floating, some sinking. Some bodies had been badly hurt, and their intestines were exposed. It was a horrible sight, yet I had to jump in the water to save myself from heat I felt all over.

As I was watching the horrible scene, someone called my name, “Miyoko, aren’t you Miyoko?” But I couldn’t make out who was speaking to me. She said, “I am Michiko.” Her burns were so severe they had reduced her facial features – eyes, mouth and chin – to a pulp.

Then I realized that bright red flames were blazing in the area from where I had escaped. Fearing that staying where Michiko and I were would mean that we would be trapped by the flames, we climbed up the river bank, helping each other.

Just as we were about to cross the bridge, we found that A-bomb victims were moving about in utter confusion on the bridge. They reminded me of sleepwalkers.

We crossed the bridge and on our way we witnessed countless tragedies. Those who drank from the water tank for fire prevention died as they tried to drink. They fell into the water, one on top of each other.

A bleeding mother was trying to rush into a burning house, shouting, “oh, my boy….” But a man caught her and wouldn’t let her go. She was screaming frantically, “Let me go, let me go, my boy, I must go.” The scene was hell on earth.

Helping each other, we came to the edge of another bridge. “I cannot run any further,” said Michiko. Yet she pleaded with me with her eyes to take her with me. I could not even give  her a drop of water. We had to separate.

her a drop of water. We had to separate.

Michiko walked alone to the temple property on the hillside about a half mile away. She was dead when her parents found her three days later. I always thought that if I had been able to help her a little more to reach the rescue center, she might have lived. My heart still aches.

I managed to get to a first-aid station. I suffered from lingering high fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and bleeding gums. Half of my hair fell out. I was on the verge of death. Keloid scars developed on my face, arms and legs. Someone helped me do knee bends so that my knees would not stiffen permanently.

I was shocked and filled with sorrow when I looked at my face in the mirror for the first time after eight months. It was disfigured beyond all recognition. I couldn’t believe it was my face. My mother would weep and say, “I should have been burned instead of you, for I am much older than you and will not live long.” She would also say, “It would have been much better if you had died at the moment the bomb exploded.” Seeing mother in such deep sorrow, I made up my mind never to grieve over my fate in her presence.

After eight months of treatment, I returned to my school only to find that the number of students had been reduced from 250 to about 50. Though I had suffered from the atomic bombing, I did not intend to stop my activities, so I studied very hard.

The horrible keloids on my face kept me from finding work after graduation. Around that time I began visiting Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto’s church, located in Nagarekawa. I faithfully attended his Monday evening gatherings for atomic bomb survivors where, listening to sermons and singing hymns with the others, my heart gradually came to find peace. With the warm help of these people and many others, I became one of sixteen young women known as the “Hiroshima Maidens” who traveled to Tokyo and Osaka for hospital treatment.

Eight years after the bombing, when I was 20, in May, 1953, I found myself inOsaka where I eventually underwent more than ten operations over a seven-month period. These operations were quite successful and, as a result, I was able to open and close my dysfunctional eyelid and to straighten out my crooked fingers. I was filled with gratitude towards those people who reached out with warm, loving hands and softly stroked my eyelid that wouldn’t shut. I returned to Hiroshima, wishing for a way to express my thanks.

Reverend Tanimoto established a facility for poor blind children without families. I and two other “Hiroshima Maidens” began work there as live-in caretakers. From morning until night, we were mothers to these children, helping them with homework, meals, going to the bathroom, and changing and washing clothes. Exactly one year later, in May 1955, my two companions left this job to travel to Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York to undergo more cosmetic surgery. For myself, I just didn’t feel right about traveling to the U.S., the country which had dropped the atomic bomb. I was left behind alone.

My one pleasure each week was attending Sunday morning services at church. The Americans I met there did not fit the image I had formed of them in my mind. They were extremely kind, and deeply regretted their country’s atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One of them was Mrs. Barbara Reynolds who later founded the World Citizenship Center (WCC) in Hiroshima. She was a pious Quaker who devoted her life and all she had to make Hiroshima internationally known. Because of her great efforts of goodwill, she eventually became a special honorary citizen of Hiroshima in 1975. Her hatred of the bombings were so strong and her caring for the victims so real, I often wondered how she could possibly be from the same country as the men who had bombed Hiroshima.

I owe what I am today to the love of Mrs. Reynolds and many other people. She is the one who persuaded and encouraged me to speak of my experience to foreigners in English even though I had no confidence in my ability nor sufficient knowledge of the English language in my view. She and many kind Americans helped me overcome the fear of speaking about my experience. I am very grateful to all of them.

Gradually coming to like and trust Americans, I realized that, had the Japanese possessed the A-bomb, we, too, would have used it. The real enemy, therefore, is not America. It is war and nuclear weapons. Those weapons must be abolished.

Nuclear weapons are manufactured by human beings. War is started by us human beings, too. Peace begins when we share our sufferings with each other. We must all strive to overcome hatred and learn to love one another. The most important task for the peoples of this world is to cultivate friendship through exchanges involving religion, art, culture, sports, education, and economic assistance.

In March 1962, just before the U.S. resumed nuclear testing and after I had been working at the home for the blind for eight years, I found a way to work at helping to abolish nuclear weapons. Through the help of Barbara Reynolds, I was chosen as a representative of Hiroshima to present the heartfelt message of the survivors of the A-bomb in person to U Thant, the Secretary General of the United Nations at the 18th National Disarmament Conference in Geneva. On the way to New York and Geneva, we visited 14 countries in five months, including the United States, England, France, West and East Germany, and the Soviet Union. Everywhere we appealed for a ban on nuclear testing.

In April 1964, I joined anther group, the World Peace Study Mission, which traveled to eight countries between April and July. When I returned home, I was shocked to find that my elder brother and his wife had died from the after-effects of the bombing, leaving their three children, who were 6, 8 and 12 years old. The children had moved to our house to live with my aged parents, expecting me to bring them up. Moreover, my father’s health was very poor, due to cancer of the stomach, and the doctor said that he had only three more months to live. Although he was a survivor of the bombing himself, he had taken care of me and had worked at the first aid station treating victims and helping to dispose of dead bodies. I began to take care of my father, and my small nieces and nephew. I devoted my life to this task.

In April 1982, when the Second Special Session on Disarmament Conference was held in the U.N., I made a third trip to the United States. My journey across America took two months. Barbara Reynolds, my guide and companion, traveled with me to Los Angeles, where we had spent an intense week introducing drawings by survivors to the people and media of Southern California. We were taken by van with those drawings, four films, 400 books, 1,500 pamphlets, 130 slide-sets, etc., from the West Coast of America to New York City. We visited 29 cities in 16 different states and one city in Canada. I made my appeal to more than 110,000 people in sixty-nine gatherings. We showed the drawings by survivors and projected our films about Hiroshima and Nagasaki so that people in North America could hear the story of Hiroshima and nuclear weapons. Three Japanese TV crews followed the exhibition, and recorded the reaction of Americans to the pictures and to my appeal for nuclear disarmament, to show on Japanese television.

Six years after the trip to the United Nations, in September 1988, I had to take five months’ sick leave in order to have breast surgery. The Director of the National Cancer Research Center said. “At the time the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the radiation released adversely affected human cells undergoing division, especially in the mammary glands where the process of cell division is at its peak when a female is between 10 and 13 years old. In those girls passing through puberty when the bomb was dropped, a cancerous seed was implanted. The female hormonal system acted to promote the growth of this cancer. Forty-three years later, the chances for having breast cancer were four times greater for women who were in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.”

I may look fine and healthy now, but my old wounds still hurt all the time. I still have the fear that I will soon have the A-bomb disease again and suffer for the rest of my life. When I get depressed and worried about the future, I try to remember my friends who were killed by the bomb when they were young. I’m sure they each had their own dreams. I feel so sorry for them when I think of how much they wanted to live. But at the same time, I can hear them saying to me that I was very fortunate to have lived and I should take care of myself in order to accomplish my mission. My mission is to continue telling my experience as a survivor, a hibakusha, appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons, talking about the folly of war and the preciousness of life, to as many people as possible. That surely will console their souls.

I am grateful for being able to live, and do what I can to make peace.

I am grateful for being able to live, and do what I can to make peace.

As a hibakusha, I am determined to continue appealing for the elimination of nuclear weapons from the Earth. That is what I must do. We survivors of the atomic bombing are against the research, development, testing, production, and use of any nuclear arms. We are opposed to war of any kind, for whatever reason.

I would like to say to young people in the United States and other countries: Nuclear weapons do not deter war. Nuclear weapons and human beings cannot co-exist. We all must learn the value of human life. If you do not agree with me on this, please come to Hiroshima and see for yourself the destructive power of these deadly weapons at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

We are at the threshold of the 21st century. It is time for us to change the international trend from confrontation to dialogue, from distrust to reconciliation, and to move towards the solidarity of nations in the world, so that every creature on Earth can live in peace on this beautiful planet. It is war itself that is wrong.

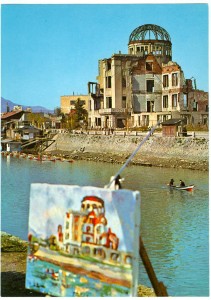

The inscription on the peace memorial cenotaph in Hiroshima reads: “Let all souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil.” That is what the spirit of Hiroshima is all about.

We must vow to do all in our power that never again will anyone have to face the tragedy that occurred in Hiroshima.

“We Shall Not Repeat the Evil.” No More Hiroshimas! No More War!

My only purpose is to appeal to everyone to work for the abolishment of all nuclear weapons, and for a more peaceful world of mutual understanding.

by Miyoko Matsubara, 1999